Hen Harrier Day is a celebration of nature and a protest against all wildlife crime. But, as its name suggests, it has a very specific focus on illegal persecution of our birds of prey, the raptors.

Birds of prey have been systematically persecuted in the UK for over two hundred years. And even though it has been illegal to kill them since the passing of the Protection of Birds Act in 1954, the persecution continues to this day. The UK’s raptors have had a pretty bad time historically: as top predators they are vulnerable when nature is depleted, and they suffered badly from the use of DDT until it was finally banned in the UK in 1984. But by far their largest problem has been persecution by gamekeepers. Some raptors take game birds and thus can damage the gamekeepers’ employers’ profits. Others, such as red kite, are no such threat but were (and are) persecuted anyway.

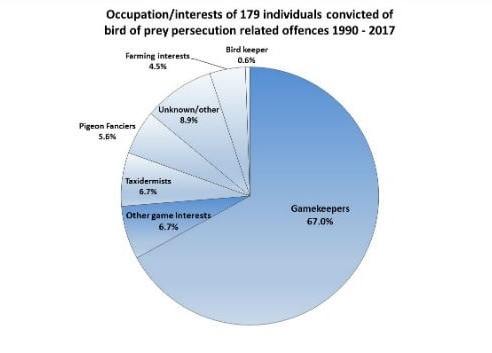

The evidence is clear that gamekeepers are responsible for more illegal raptor killings than any other group in society. Many wildlife crimes take place in remote areas, far from prying eyes. Prosecutions are rare but do happen. And here’s what the figures compiled by the RSPB tell us, shown in the figure.

The consequences of persecution have been devastating. The white-tailed eagle was hunted to extinction in the UK in the 1800s but reintroduced to Scotland’s west coast in the 1970s and to its east coast more recently. More recently, a number of birds were reintroduced to the Isle of Wight. However the white-tailed eagle is still subject to illegal persecution; two satellite-tagged birds disappeared in suspicious circumstances – over grouse moors – as recently as November 2019.

The red kite too was hunted to near-extinction in the 19th century, leaving only a tiny remnant population, in mid-Wales. Despite protection this population was unable to re-colonise more widely, but a popular and successful reintroduction scheme starting in the Chilterns has made these birds familiar again to many. But red kites are now, again, persecuted, even though they do not predate game birds. The mere fact of their being raptors is enough, it seems, and there have been poisonings and shootings near release sites in Scotland and Yorkshire in particular.

There is more. Scotland’s iconic golden eagle is subject to intense persecution over the grouse moors in the east of the country; last year a rare bird from the southern uplands was shot only miles from Edinburgh and the corpse dumped at sea. Peregrines are absent from many places where they should be flying free: ironically many people are more likely to see them on steeples in cities than in the countryside. Buzzards are routinely killed, and even the merlin is too often caught in spring traps intended for other creatures.

Much of this used to happen unseen, with even local people unaware of the scale of the illegal slaughter. That is now changing: more birds are satellite-tagged. Although the proportion tagged remains low, that proportion can reveal much about the unseen damage to the whole. Raptor study groups have also brought information to the public’s attention and one blog in particular, Raptor Persecution UK, has done a huge amount to pull together all the evidence and increase public, media and political awareness of the scale of this criminal activity.

The first Hen Harrier Day, in 2014, was another stepping stone, as was publication of Mark Avery’s book ‘Inglorious’ in 2015, and in 2016 a petition to the UK Government and Parliament calling for driven grouse shooting to be banned was signed by well over 100,000 people. A similar petition in 2019 attracted nearly as many signatures in just a few weeks and awaits debate in 2020.

Thanks to all this effort, and much more, public and media awareness is much higher than it was just a few years ago. Gone are the days when the August press had only silly-season stories about the ‘Glorious 12th’ to mark the start of the grouse-shooting season. Every story now – and there are more of them – includes criticism of this controversial ‘sport’.

Photo credit: many thanks to the RSPB for the picture above.